Terada-Mokei was established with a view to

exploring the potential for modeling, which

is created by scaling things down and giving

them detail, through models. This reflects our

belief that when real items are replaced with

models, the latter have an essence of reality,

stuffed with dreams, and the potential to become

more vibrant -- better word in my opinion than

their originals. We also consider it important

to enjoy the process of assembling models.

Terada-Mokei also hopes to convey the fun of

assembling models and imagining the same.

"Replicas" and "models" are different.

Replicas and models are often confused for one

another.

Replicas are substitutes that you accept when

your desire to have the real thing cannot be

fulfilled. That is to say they are imitations or

reproductions. For example, a replica of the

mask of Tutankhamen or Michael Jackson's

jacket. At Terada-Mokei though, we don't

think of "models" as replacements, but rather

a product that represents, in a positive manner,

values or points-of-view different from the

actual object. For example, models of test

airplanes for wind tunnel experiments or

molecular models of the amino acid sequence,

the model itself exists in that representation and

reason for the model. These are what are defined

as "models".

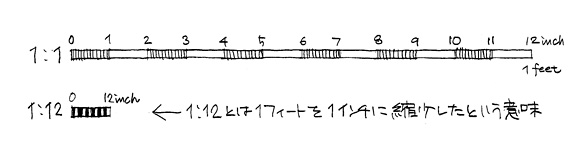

Scale

Models come in a variety of scales. For example, globes are 1/300,000,000 in scale.

Luxury cruise ships come in 1/350 or 1/700th scale. Architectural models and drawings are typically 1/50 or 1/100 in scale. On the other hand, some models are much larger than their originals. Cellular sequence models and models of small insects can be 10 times or 100 times larger than the actual object. There are full-scale models as well. School science room skeletal models are usually actual size.

In another example, the railroad model "N scale" is 1/148 to 1/160 scale in size. The ratios might seem odd but, this is the scale inversely configured to fit the width of the tracks set at 9mm. And then there's plastic model tanks, which are mainstreamed at 1/35th scale. The scale in this case was decided upon so that two "C" sized batteries would fit into the body of the tank. In addition, models in the 1/12th or 1/48th range adhere to the Imperial Units rule of feet and inches. 1/12 represents 1-foot reduced to 1-inch, while 1/48 represents 1-foot reduced to 1/4th an inch (or a quarter inch). As the Imperial Units rules are originally based on a duodecimal system, the denominator is a multiple of 12.

However, there are models which have no set scale--like toy cars. For ease of product handling, box sizes need to be standardized. Therefore since both small sports cars and large fire engines have to fit in the same sized product box, their sizes are standardized as well. And since all the toy cars vary in scale, they aren't really scale models.

That said, model paper airplanes and similar objects are, to an extent, converged into one size, so that they are able to fly. Understanding the Earth's gravity, the properties of the paper, and the relationship of air density, we can deduce what that size should be. Though it is a non-scaled item nor is the airplane based on the real thing, because the scale is based on rationale, we called it a scale model.

There is a reason behind setting scale, therefore upon perceiving said scale, we can understand the goal and intended purpose of the model's creation. So conversely when you need to decide which scale to use, you need to be careful. Furthermore, depending on what is it you are trying to represent or what message you are trying to express to others, you have to make a decision on what kind of materials and technique you will employ.

Scale conversions are a little confusing perhaps.

For example, when one converts a 1/100 scale model to full size, it translates into a volume of [1/100^3, or] one millionth (1/1000000). A 1/ 100 scale model apparently feels a million times smaller than the real thing. The difference in the numerical notation is perceived threefold. I believe the difficulty/problem arises in having to use one-dimensional notation to deal with a three-dimensional object.

Details

I used to think that the ideal scale model would be one that represents the real deal in shape and element in every way, whether you looked at it with the naked eye, a magnifying glass or a microscope. Well if shrinking lasers existed, they would be the solution of all the problems of scaling things. But they don't exist, so all we can do is try to follow in the footsteps of the peerless skills of those like Swiss precision watchmakers. That said, creating the perfect model that grabs people's attention is not about creating perfection. Constructing the details and controlling density of a model is crucial. Any way you work it, appreciation comes from a visual context, so detailing things the human eye cannot or will not pick up is pointless. Rather those models which are low on elements and leave room for the imagination give birth to 'reality'. The 1/1 scale human eye can appreciate models. This is where scaling mediates, by using your imagination to compensate between you and the difference in model scaling. I think that's the joy in appreciating a model. In my opinion, deciding on how to construct that compensation -- that is to say, figuring out the details -- is the fun in creating a model.

Distortion

As a method for resolving the problem of detailing, we can use a form of distortion. I believe there are two methods of going about this.

・The Distortion of Color

About the time I had gotten started in

architecture, a senior colleague of mine taught

me: "Color tends to look lighter when applied

to a larger area." That sounded reasonable;

compared to smaller area color samples, large

walls appeared lighter and brighter. My thought

on the subject is that generally when viewing

samples, we pick them up and hold them at

range of 10cm or so, while large walls are

viewed at a distance of several meters. It won't

fit into our field of view otherwise. So we step

back. Thus color looks lighter from a distance.

I think that's because between the human eye

and the object being viewed, there are layers

of atmosphere and the minute particles in the

air that block our vision, rendering the color

lighter. Similarly in my opinion, in Japanese-

style paintings, backgrounds are painted

with a lighter color ink to create a blur which

emphasizes a sense of distance, a technique

called "atmospheric perspective".

Viewing a small model is like viewing the real

thing from a distance, therefore thinning the

color of the model by a degree of viewing the

real object through air density, increases the

realism of the object. For example, if you view

a 1/24 scale model from a distance of 1 meter,

that is the same as viewing the real object from

24 meters back. With 24 times the atmospheric

particles obstructing view, if you increase the

luminosity and decrease in the saturation, the

feeling of the work will be just right. It's quite

a pleasing effect. Moreover, as it is your vision

that is blurred by particles in the air, color is not

the only thing that appears blurs. Shapes and

contours also blur. So by not defining the model

so rigidly, it is possible to create a more realistic

model.

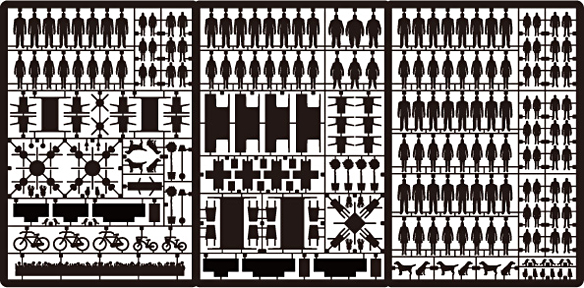

The catalyst for producing this product was

the construction of architectural models at the

office on a daily basis. It was a design office,

so that was normal, but I came to realize that

to improve the visual aspect of architectural

models, people, furniture, trees lining the

streets and so on, known as "architectural

model accessories", were as important as the

architecture itself. However, it often took me all

night to construct a model. I used to run out of

steam mentally and physically when having to

make the key "architectural model accessories"

at the break of dawn. Moreover, I hesitated to

ask my red-eyed staff to "line some bicycles

along here", as that would have made me sound

like a drill sergeant.

Subsequently, I thought if such accessories

could be mass-produced in advance, it might

help in getting a little more sleep.

If I could make people happy through

these "architectural model accessories," without

constructing actual architectural structures, I

thought it would be my great pleasure.

The clue to commercializing them came by way

of plastic models.

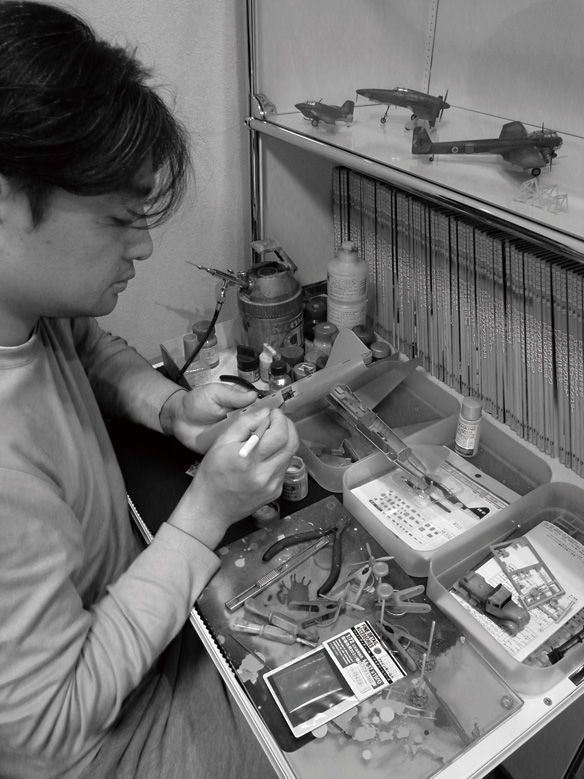

I love plastic models. Even these days, after I'm

finished with work, I enjoy the steady process

of assembling them. (At the office, I work on

paper models, then return home to refresh by

assembling plastic models...)

The interesting thing about plastic models is that

there are two degrees of completion.

For customers who buy plastic models at retail

stores, the model is "unassembled", but for

makers, who line them along the shelves of the

same retails stores, they are assembled "finished

products." More so than the completion of

the parts, a combination of the strengths of a

striking box-photo and the assembly instruction

(what were called "blueprints" when I was boy)

graphics significantly impacts the completion

of the finished product. If there is a feeling

of incompleteness in any of these, motivation

to assemble the model will be low. With top-

class manufacturers, that sense of completion is

high, which in turn greatly affects the customer

excitement even before assembly.

Our "ARCHITECTURAL MODEL

ACCESSORIES SERIES " are like plastic

models in that you have to assemble them,

so the design and layout of each part was

painstakingly created so that the excitement of it

is constant throughout the process of assembling

them. Parts that can be properly assembled,

exciting shapes that encourage assembly, and

the precision processing of manufacturing, these

three points are repeatedly recalibrated into

prototypes until they are correct.

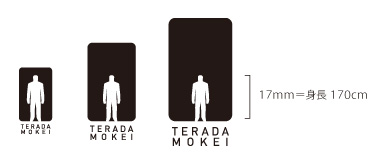

The question was how should I distort the 1/100

scale world to bring it to life. If you look at the

1/100 scale human figure used in the product

logo, it is quite different from the figure of a

real human. The figure is deliberately distorted

so it will be able to represent the world in a 1/

100 scale. So it becomes the rule to distort all

the items in the 1/100 scale world in the same

fashion. With that the representation of the

world in 1/100 scale is complete.

Moreover, the instructions on the back are quite

painstakingly written out. Within the space of

a postcard, our goal is to create a little fun by

having customers imagine what the lives of the

little 1/100 scale humans are like. With that

in mind, I took the time to design not just the

product but the assembly instructions as well.

Why 1/100 Scale?

The 1/100 scale is the most popular scale when

it comes to architectural building models.

From models of houses and apartments, to

public facilities and shopping centers, all

these different sized buildings are possible to

represent. In addition, since interiors, furniture

and similar objects can also be represented on

a generic scale, accessory sets have become 1/

100 in size. Also, I think the 1/100 scale makes

it easy to create various abstract and distorted

items. However the 1/200 and 1/300 scales are

too small making for very little room to work

within. As for the 1/50 and 1/30 scales, I'm

concerned about the texture and the detail of the

shapes. I think that 1/100 is the perfect scale for

creating, as it creates just enough difference in

the objects, such as between human poses and

gestures, a folding chair and a wooden chair,

and a Shiba Inu and a Golden Retriever.

Why isn't there any architecture involved?

When I first began my architectural courses,

the first thing that was said to my classmates

and me was "Architecture should bring joy

to people, designing such architecture in the

future will be your duty." An architect's calling

is to make people happy through architecture.

That's a lot of pressure. Taking those words

to heart, I set forth to build models with the

intention of presenting them to the clients, yet

when I showed clients the models the first thing

they would say was something to the effect

of "Oh, you've recreated the whole family!"

or "That's our dog in the garden!" In essence,

it wasn't the architecture they were thrilled to

see but the accessories. That brought out the

little devil in me, and I took pleasure in posing

the figures I would show the clients. Through

the shapes and poses of the accessory figures,

I believe that the architectural goal of bringing

happiness fulfilled. Thus, the accessory kits are

not architecture. So even without architecture, if

people can be happy with the accessories, then

I am happy as an architect. Architecture is the

foundation of Terada-Mokei, which is designed

at Terada Design.

It's okay not to assemble it

I designed the accessory sets as kits you can

assemble.

As the accessory kits are assembly kits, I

designed them to be fun for you to do so,

however I would be just as pleased if you

are so inclined to just enjoy envisioning their

unassembled potential as well.

As with assembling plastic models, the most

exciting part is looking over the "blueprints" and

imagining their potential. If it makes you happy

just to hold the package, that would make me

happy as well.

The character in the product logo is a 1/100

scale person who always appears in 1/100

ARCHITECTURAL MODEL ACCESSORIES

SERIES. I named him "Genki-kun." "Genki-

kun" does not "Mr. Energy" but "Mr. Standard."

There are various units of length. In ancient

times, cubits in the Egyptian era, and feet,

inches, shaku and suns were also units of

length. Although they have been used until very

recently (or even still), a metric system has

been established with international unification

in mind. So the "standard meter" exists to

strictly define the length of 1 meter. The origin

of the name "Genki-kun" comes from his

representation of the global standard for 1/100

ARCHITECTURAL MODEL ACCESSORIES

SERIES. He defines the global view at 1/100.

Moreover, Terada-Mokei hopes to create

something serving as a "standard" for models

and scales in future. So, I had "Genki-kun"

appear in the logo. Even though the logo size

may change, "Genki-kun" remains at 1/100 as

the "standard". When the logo size changes, the

design follows suit.

"Genki-kun" has a family. They are his

wife "Mrs. Genki", his son "Genki Junior"

and daughter "Genki-chan" and his pet "Genki

Doggy", who will all appear eventually.

Naoki Terada Architect, designer, modeler, culinary specialist

1967 Born

1989 Graduated from Architectural Department, School of Science & Technology, Meiji University

1994 Completed the diploma course of the Architectural Association School of Architecture (AA school) in the UK

2003 Established Terada Design first-class architect office

2011 Established TERADA MOKEI